HomeEventsBlogFloor Plan Fit CalculatorCareers

Lifestyle

Independent Living

Health Services

Gallery

About

Contact

A secret Mission- Major Mike Golas, US Air Force

After graduating from the USAF Academy in June 1966 I went to pilot training at Laredo AFB for one year. I was fortunate to have done well enough in pilot training to get assigned to the F-4 Phantom II, but for some silly reason they put new pilots into the back seat of the Phantom, so after checking out in the F-4 back seat I went to Vietnam.

In this one-year tour, mid 1968 - mid 1969, I was assigned to three different bases in Vietnam, starting off at Cam Rahn Bay, going to Danang, then to Phu Cat air bases. My missions were primarily close air support of our ground troops in the south, interdiction of enemy supplies heading from North Vietnam to their troops in the south, and destruction of combat supplies and factories in the north where I either protected B-52s from enemy fighters or conducted bombing missions in an F-4.

Since I was young and invulnerable, I volunteered for a second one-year tour to go straight into the front seat and then to Udorn Royal Thai Air Force Base in northern Thailand, where I spent all of 1970 flying combat missions in Vietnam and Laos. It was here that I had one mission that I will never forget. While flying F-4 Phantom fighters at Udorn RTAFB (Royal Thai Air Force Base) in 1970, my next day’s schedule said that I was part of a small group who were told to get some sleep and come back for a midnight mission. In the preflight briefing, we were told to go a bit south of Hanoi in North Vietnam and orbit until called on to intercept any enemy fighters that might get in our area. There was no other information about why we were there or what else might be going on, as that was top secret information.

During this mission, I did not intercept any enemy aircraft but observed a bright fireball heading towards Thailand, which turned out to be one of our aircraft that had been hit by enemy fire and was attempting to reach friendly territory before bailing out. I did some serious maneuvering while circling the area to avoid ground-fired anti-aircraft missiles from locking onto me. After receiving instructions that the mission was completed, we returned to Udorn base.

When I was accomplishing my post mission debrief, the debriefer said he could finally tell me what the secret mission was. He said I was protecting a mission to rescue some of our prisoners of war in a POW camp in the Hanoi area. This was the greatest high I have ever felt as most of these POWs were my fellow aviators putting up with terrible conditions and cruel treatment by the North Vietnamese. Regrettably, the next thing he said was that the prisoners were not in the camp. They had evidently been removed a week or two before this mission occurred. This was one of the greatest lows that I have ever felt.

Although initially disappointed, I later learned that our mission proved to the North Vietnamese that we had the intelligence and the capability to raid their POW camps at will. They became very concerned and began treating our POWs much better. Knowing this made the effort worthwhile and a mission that became my most memorable.

H-E-L-L-O Vietnam- CWO4 Robert Williams, US Army

After finishing Flight School and knowing that I was the best pilot out there (at least in my mind), I departed from Travis AFB (CA) for a 20-hour, two fuel stops flight to Vietnam. We landed in Saigon where the flight attendants asked us to disembark. The outside conditions were unbearably humid, with temperatures and smells that I had never experienced before but that I was soon to learn would be the new norm for me during my two tours (24 months). After getting off the plane I was immediately transferred to a bus that took me to Long Binh, approximately a 30-minute drive. The side windows of the bus were covered with heavy-duty mesh, which I later learned was to prevent grenades from being thrown into the bus and not to keep me from escaping the bus as I had envisioned. I arrived at Long Binh safely, and somewhat sound, although mentally, I was confused and unsure of what to expect next.

I was taken to a “Replacement Center”. (Yup, that means just what it sounds like.) At the "Replacement Center," I would be replacing individuals either going home or not returning. My stay at the center lasted two days before I received my orders. Shortly thereafter, I, along with two or three other pilots from flight school, were in the back of a Huey, receiving an overview of Vietnam…, “a grand tour” as the pilot announced. However, our destination was Cu Chi, located roughly 35 minutes northwest of Saigon by a Huey helicopter.

Upon arriving at Cu Chi, which was larger than anticipated, we observed numerous Hueys and Chinooks. Shortly after arrival, we were escorted to speak with the Battalion Commander. Standing tall and keeping our mouths shut, we waited in his outer office. We began to interact with his clerk, a pleasant E-5 who provided valuable information. He informed us that some personnel would remain at Cu Chi while others would be assigned to a “safer” location at Tay Ninh. He stated that Tay Ninh experienced much fewer rocket and mortar attacks. Consequently, I, along with several others, decided that Tay Ninh would be our preferred destination.

Shortly thereafter, we were summoned to the office of the Battalion Commander. Given his busy schedule, he greeted us briefly and granted me and two others our preferred location at Tay Ninh, which made us happy. On that same day, we boarded another Huey and traveled to Tay Ninh. I commenced flying missions the next day. There was indeed much for me to learn. During my first day of flying, our aircraft sustained multiple hits, which was quite an unexpected introduction and quite a rude awakening. No more long hours of training, this was the real stuff!

Over the next several days and nights, we unexpectedly experienced continuous rocket and mortar attacks in our compound, certainly more than “the occasional attacks” so described by the “nice guy” Battalion Clerk. This led me to question whether the clerk had been entirely forthcoming.

A few days later, the Viet Cong launched even more rockets and this time destroyed our warm water shower building. I was beginning to think they had a vendetta against my roommate and me because they also blew up and destroyed our “hootch” with both of us inside! So much to our dismay, we both had earned a Purple Heart. However, my biggest lesson learned from Vietnam…DO NOT ever trust a Battalion Clerk!!

Vietnam Era Engineer- Captain Ken Bottoms, US Air Force

Upon graduating from college during the Vietnam War, my first employer indicated they could secure a draft deferment for me due to the nature of the national security projects I would be working on. However, the draft board in my small East Texas hometown declined their request. Consequently, I explored opportunities with each branch of the military. Uninterested in serving in the Army or Marines wading through rice paddies or treading through jungles, and unable to swim, which precluded the Navy, I found appeal in the Air Force recruiter's offer. He assured me of an "exciting electronics design job in California” a promise that ultimately proved to be false. Nonetheless, I enlisted on April Fool’s Day, 1968 and subsequently departed for Officers Training School (OTS) in San Antonio.

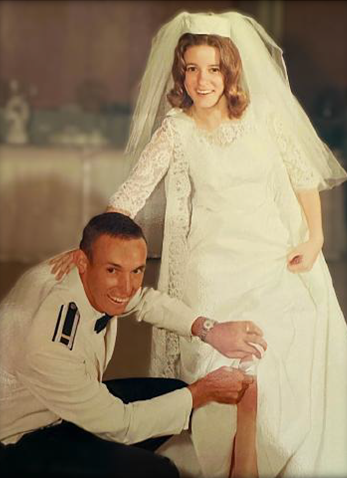

Anne and I got married two days after I graduated from OTS. Her mother was a nervous wreck thinking that I might have to leave immediately for my first duty station after graduation and all the wedding plans would fall apart. The Air Force gave us about a week for a honeymoon and then we loaded up our worldly possessions in the back of my red Mustang convertible and headed to Tinker Air Force Base in Oklahoma City (not California as promised by the recruiter).

My job for the first two years at Tinker AFB was to correct design flaws in weapon systems which were not working properly in Vietnam. Most of my projects were to improve the reliability of electronic circuitry. However, one assignment was to reduce the failure rate of the inertial navigation guidance system in the AGM-28 Hound Dog Missile. When the missile is launched from a B-52 bomber, its navigation system guides it to a target such as an anti-aircraft site on the ground. This complex system was failing in flight, resulting in missed targets. It turned out that gyros inside the missile were the cause of the failures. I found that small ball bearings inside the gyros were freezing up. I told my supervisor that I’m an electronics engineer, “I know nothing about ball bearings.” He said that was no excuse. “Fix it.” So, after some research, I learned that the most respected ball bearing expert in the country was a professor at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). So, I traveled to Cambridge, Massachusetts, and he helped me come up with a fix for the problem.

I had many other interesting projects, especially in my last two years when I worked on the Air Force Worldwide Airborne Command Post electronic systems. The Air Force keeps a General in the air 24 hours a day, 7 days a week with all the electronics and crypto gear needed to launch nuclear missiles and fight World War III without landing. I was the project engineer for installation of the first minicomputer on the Command Post aircraft. It was required to establish a data link from the aircraft to a computer in an underground complex near Washington, DC…but that was for National Defense, not for the Vietnam War!

Cold War Formation Flying -Colonel Ed Roberts, US Air Force

Reconnaissance has been a part of military operations since the beginning of conflict. The story is told of two cave men battling daily from opposite sides of a river. Every day the men came to the river to get water. They threw rocks across the river to drive the other combatant away and claim all the water for himself. The battle ensued until the warriors ran out of rocks that were available along the bank of the river. One day one of the fighters ran out of rocks well before his opponent. He was forced to retreat. Not one to give up the fight the battered cave man wondered what happened. He knew the river current only brought in a limited number of rocks each day. Why did he run out of rocks while his opponent still had ammunition? That night he slipped across the river hoping to answer the question. He found that his opponent was gathering rocks from all around and moving them into position for the next day’s battle. Reconnaissance paid off, the next day both men had an ample supply of rocks ready for the battle. History does not record the outcome of this conflict. But it does show that reconnaissance has been around for a long time.

During the Cold War, the United States used many methods to learn about potential enemies and their capabilities. One of these was Airborne Electronic Reconnaissance. We flew near the borders of the country of interest and listened to any electronic emissions we could receive – radar, radio, etc. I was a part of this effort in the 1960s. Our squadron was equipped with specially configured C-97 aircraft.

On one mission, we were “on station” flying over international waters – won’t say which waters but if we had bailed out, we would have found that the waters were very cold.

The pilot informed those of us working with the various receivers that we had company. A couple of us went to the bubble window of our aircraft which allowed for 180 degrees of viewing. There, flying in perfect formation with us was an interceptor aircraft. The insignia on the interceptor was somewhat different from the insignia on our aircraft. We had a white star inside of a blue circle. The interceptor insignia was a plain red star.

Our intelligence officer had given the crew leader a 35 mm camera to use in case we were intercepted. One of our crew positioned himself in the bubble window to take a picture of the interceptor. As he zoomed the camera in on the accompanying aircraft, he reported that the “backseater” in the interceptor had his camera focusing on us. Everyone does reconnaissance!

Special thanks to Larry Beck for gathering and submitting these stories to honor these brave veterans. These stories and many more can be found in a series titled, “Who Be Us,” a project resident Larry Beck spearheads. The series now has several editions, each with a different topic that highlights the lives of those who live at Stevenson Oaks.